I’m starting this post with a tangent. My Substack, my rules.

***

In late 2019 I was briefly the editor of Querelle magazine, an obscure LGBTQIA+ student publication associated with Queer Collaborations – an equally obscure student conference.

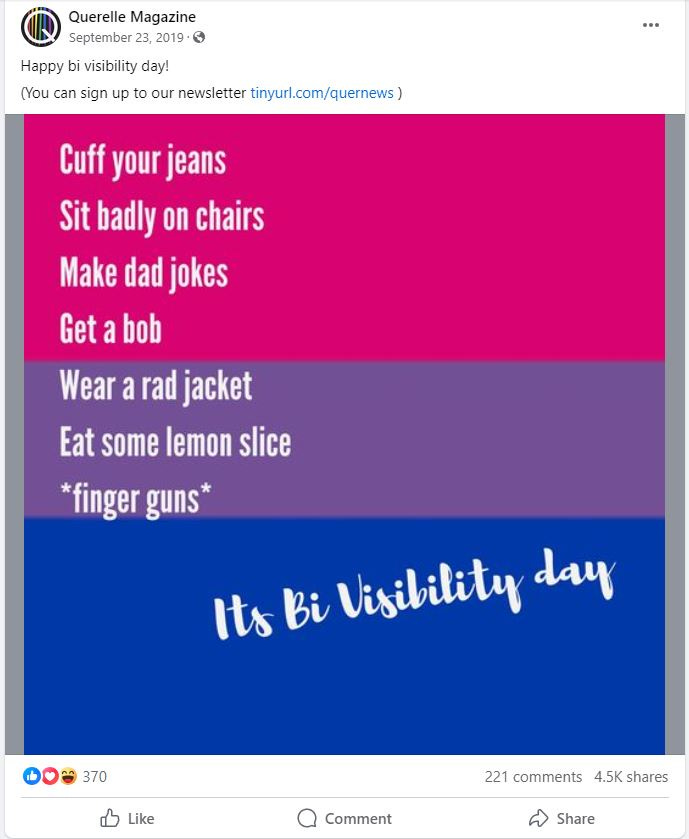

When bisexuality visibility day rolled along I created a, frankly terrible, graphic on Canva to mark the occasion.

Back in 2019, at least in the queer youth corner of the internet, there were heaps of memes going around about defining “bisexual culture”. This included denoting a random array of actions, activities, items and behaviours as “bisexual culture”.

According to the internet culture of the time, wearing ‘rad’ jackets, sitting weirdly on chairs, cuffing your jeans, having a bob, doing finger guns, and enjoying lemon slice were all “bisexual culture.

So on Canva I made a crude version of the bisexual flag, and wrote a list of these allegedly bisexual things and activities.

I didn’t know I was cooking.

The post was popular. Not exactly viral, but it got a few thousand shares on Facebook, back when it was relevant. This was huge for us. The people sharing this post seemed to like the content. If we got any hate for it, we didn’t notice it.

Awesome right?

Wrong.

The sudden interest in Querelle’s Facebook page was flagged as suspicious by Facebook and our content was suppressed for ages.

Ultimately, we did what most people would think would be good social media. We tapped into the zeitgeist. We referenced memes and conversations our audiences were engaged with. It spoke to an audience that supported our message, and led to a spike in organic engagement.

Isn’t this, like, what we are supposed to do?

***

When I started my current role, I made a fairly controversial rule for our social media content: no memes.

In a document I drafted covering the communications needs of the organisation I wrote this.

“Despite what some social media marketing agencies seem to think, replicating memes already in the zeitgeist does not engage audiences. If anything, it disengages audiences, particularly digital natives (Gen Z and Millennials). Its cringe.”

Oh my god, there is nothing worse than companies trying to use memes or trends.

For a while I kept getting ads on TikTok, with some influencer I neither knew nor cared about, that claimed Pepsi was in its “new era”.

Sorry, what era? Hot girl era? Skibidi era? Tomato girl era? Recession-core era? It’s giving “how do you do fellow kids” energy.

I like understated, stripped back vertical video content that focuses on communicating interesting or important information from reliable people without too many bells and whistles. It’s not that hard.

***

The TBH Skincare debacle is a perfect example of why companies should have a no-memes or trends policy for their social media content.

For those living in a social-media free utopia, in a TikTok video TBH Skincare employees spoofed the “boots and a slicked back bun” trend.

In the video employees described themselves with phrases such as "Gen Z boss in a mini", “fake tan hands and a hoop” , and most egregiously "itty bitty titties and a bob”.

When I saw the video, I thought it was cringe. It was Ohio. Negative-aura. Exactly the kind of content I do not want to create at work.

Regardless of the communications sins I believe TBH Skincare committed, they did not deserve the truly violent and misogynist backlash they received from Andrew Tate and his legion of losers.

Sure, you can spin a communications failure like this in your favour.

If supporting TBH Skincare triggers Andrew Tate, I’ll buy out the warehouse.

Being able to retrofit communications fail into communications win is not good communications.

It doesn’t undo the fact this video put TBH Skincare employees in danger and puts their professional reputation at risk.

Lawyer Roxanne Hart made a brilliant TikTok about the potential safety issues and legal issues a video like this could cause.

“Can somebody please tell me what the hell those employees got out of being featured in this video?” She said.

“I can tell you who might benefit, the shareholders of this company, the owners.

“They may have gotten something out of it.

“The employees, they don’t get anything out of it.

“This could be limiting for their careers.”

Hart’s video highlighted how communications staff, or whoever is in control of an organisation’s social media, has a duty of care to ensure the safety and professional reputation of staff members featured in content.

I make weekly vertical videos at my job, which feature real employees from my organisation.

I respect my colleagues as professionals. I do not pressure anyone to be involved in our videos. I respect some people cannot be involved in these videos for safety reasons, or personal preferences.

Even if someone is eager to be involved in one of our videos’, creating content is not their job, and it should not interfere with their work.

One really big part of extending respect to the colleagues who are volunteering to be included in our social media content is to not make them do embarrassing things that could undermine their reputation.

Ultimately people are not going to our social media sites to see our staff do embarrassing dances or trends.

We’re not Amy Poehler, nor are you.